The Question of English

In an interview, Dalit activist and writer Prof. Kancha Ilaiah said, “English should be introduced in all schools and colleges by Telangana government as that is the only way to bring equality among all sections of society and empower people from downtrodden sections. Also only english education can provide employment opportunities to youth in an era of modern technological developments.” Prof. Ilaiah made this statement while demanding that the Telangana government introduce English medium in all schools and colleges and urged parents to send their children only to English medium schools.

Anyone who has interacted with the linguistic reality of India, and I am guessing most of us have, from one end or the other, cannot deny the validity of this aspiration for English. English has fortunately or unfortunately become the most compelling way of letting children access knowledge in the economies that we have created. As a third generation user of the language, I have exploited it at every point of my life in a bid to not be excluded. At all kinds of youth gatherings, at malls, banks, restaurants, universities, new-age book stores, college festivals, social media wherever. Everywhere I went. The English card has never let me down. It still doesn’t.

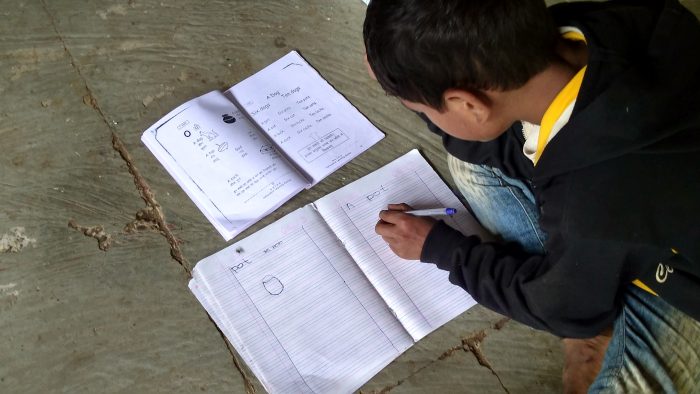

I cannot begin to imagine thus, the ways in which it excludes those who have historically been refused entry into the realms of this language through barriers, of caste, class, religion and gender. As has become increasingly evident, the higher-education system in India as well as the formal job sector are highly alienating towards the non-speakers of English. As an English Teacher at an Adivasi school, I have struggled often with the question of what form of education could be relevant for my students. My students however are marred by no such conflict. They are clear as to what they want out of me. They are certain that they must learn English while I am around. Their reasons are varied. Some want to learn it to go to cities, some for jobs, some to read the English books in the library and many so that they can understand what the volunteers who come from different cities speak amongst themselves. The last reason is especially compelling to them.

Alongside, the presence or the lack of knowledge of English has also resulted in the creation of rigidly divided social groups. I have realized in the last few years that my life in a metropolitan city hardly required me to interact with non-english speakers on an equal footing. Apart from mixed forms of interactions in University spaces, and unequal interactions with those who provide different services to us in our homes, streets and workplaces; our interactions in cities are largely insulated and limited to those dressing, speaking and thinking like us. My understanding thus is that, the aspiration for English is not just to be included within the realms of economic and social progress, but that it also represents a very real desire to be acknowledged, to not be sidelined, silenced or shamed by this prosperous quarter of the population.

Does an acknowledgement of this aspiration then mean a movement towards English Medium Education? In that case, one can also not be ignorant of the compelling reasons supporting the cognitive and cultural arguments of Mother Tongue Education. A child’s natural learning trajectory requires that she be surrounded in a linguistic environment which is expressive of her experiences and culture. The absence of this and the insulation of the child in an alien linguistic setting are bound to cause grave cognitive and cultural loss to her. Both the arguments are fairly articulated here by noted linguist Ganesh Devy, “English is a powerful language. Yet, it is an established scientific principle that early education in the mother tongue helps in the proper development of cognitive faculties and the ability for abstraction. The cumulative effect of the rise of English schools in India on Indian languages is going to be negative. That would lead us into difficulties while conceptualising our cultural history. When a large number of such children get into positions of authority, their collective amnesia about cultural history can pave an easy way for false historical narratives and a fascist political environment.”

Why is it however, that despite the advantages of Mother Tongue Education, there has been a surging demand not just for English but an English Medium Education? This demand is most acutely reflected in the rising percentage of the number of children being admitted in a range of private English medium schools, from low fee private schools to elite high cost private schools.

I am perplexed however as to why these two ideas have come to be so strongly pitted against each other. Why is it that in the minorities’ argument, there is not just a disagreement with the proponents of Mother Tongue Education, but instead intense hostility and distrust too? The effort to find answer to this question often takes me back to this quote featured in the noted black educator Lisa Delpit’s book Other People’s Children, “My kids know how to be Black—you all teach them how to be successful in the White man’s world.”

This quote has represented to me, the voice of a parent often told what is best for her child with the well-intentioned assumption that she wouldn’t know better. Has the English speaking, decision-making group also in a similar sense caused grave alienation to the masses, whose primary hopes of progress lies in the access to the dominant language? It often appears as if the burden of cultural preservation and Mother Tongue Maintenance has fallen just on those who have anyway been left on the margins of economic and social development. Is it not essential then, that the speakers of English do not assume the sole guardianship of English, taking decisions in isolation of the voices of those whose lives they don’t lead?

Finding ourselves in the middle of this linguistic clash, what are the possibilities that we can then begin to imagine ways of thinking which are accommodative of both the sides of this argument? Where the maintenance of Mother Tongue is no more the burden of a particular group, but is rather a necessity for all. Especially for those who have been falsely privileged into treading far into the realms of cultural and linguistic amnesia.

There are no easy solutions to this issue. This article however, is an effort at inviting dialogues on the subject, with the appeal that we recognize seriously the indispensability of English in attaining progress in the national economy and yet find ways of dialoguing on efficient multilingual systems, where English as a subject and a skill finds a sharp and committed focus.

References

- Introduce English in all schools, says Kancha Ilaiah (2016, August 8th) The New Indian Express. Retrieved from http://googleweblight.com/i?u=http://www.newindianexpress.com/states/telangana/2016/aug/08/Introduce-English-in-all-schools-says-Kancha-Ilaiah-1506820.html&grqid=flSFolhY&hl=en-IN

- India might become an educationally failed nation: Ganesh Devy(2017, June 8). The Financial Express. Retrieved from http://www.financialexpress.com/india-news/india-might-become-an-educationally-failed-nation-ganesh-devy/707203/

- Delpit, L. (2006). Other people's children: Cultural conflict in the classroom. The New Press.

Congratulations. A very balanced paper on “The English Question”.

I don’t need a debit card or a credit card, I need the ‘English card’ to get my work done in this land of thousand Indian languages. Dial a number of any office or a call centre in India and speak in English with an artificial British or American accent, you will get your work done. It never fails. All of us know this trick, but are afraid of admitting it in public.

The English knowing elites of this country are apprehensive of their power and position acquired by them with the help of an alien tongue. What will happen to them if the ‘common people’ get an access to the resource essential for climbing the economic and social ladder?

The vast majority of our population have a right not to be “sidelined, silenced or shamed’ for not knowing English. How many of us are aware of the despair and agony of the young people who come to the big cities for higher education after completing their graduation through the medium of their mother tongue? Privately, they curse their teachers who did not teach them English adequately in the regional medium schools where they had undergone a ritual called English language teaching.

Can’t we teach English to our children without causing ‘grave cognitive and cultural loss?’ Can’t we empower them linguistically without depriving them of the benefits of mother tongue education?

Way back in 2005, the NCF Position paper on English Language Teaching suggested that English should occur in tandem with the first languages(s) of the learners at the lower primary stage and the artificial difference between languages should be removed from the class routine. But who cares? English and the mother tongue, never shall the twin meet in our vernacular medium primary schools!

The ‘indispensability of English in attaining progress in the national economy’ and ‘the use of the mother tongue for the cognitive, cultural and social growth of our children’ should not be mutually exclusive, they should be complementary to each other.

Thank you very much for for such a detailed comment. All the points that you make, regarding the agency of English, the pain associated because of exclusion, the existing power equation are extremely relevant to the debate. These are all combined with an extremely challenging reality on the ground. This makes it all the more essential for us to continue having conversations around the issue. Thank you for participating.