Narrative Development in Young Children: The Link between Oral and Written Storytelling

Most Indian classrooms and curricula focus almost entirely on teaching children the form of writing – spellings, punctuation and handwriting. They forget to teach children to write in order to express, to communicate, and to narrate. Yet, these are the key functions of writing, the reason most of us write. We need to focus on these functions in our early language classrooms, so that children can express themselves proficiently in the written form for a variety of purposes.

In this blog piece, I argue that children’s oral language development is related to their attempts at writing. Therefore, one key way to support children’s writing is to support the development of their orality. One of the key aspects of oral development young children master during the pre-primary and the early school years is the art of telling a story – a narrative. Giving children opportunities to listen to - and discuss - stories, to tell stories of their own, and to express these stories in writing is important for supporting the development of both orality and writing in young children.

What is a Narrative? Why is it Important?

A narrative is a story in which a speaker or a writer relates an event, incident, or experience. Western scholars report that children’s sense of narrative emerges early in life, because narratives are ways by which we remember/make sense of events in our lives (Applebee, 1978; Bruner, 1991; Wells, 1986). They help young children to develop concepts of time – what happened first, and what came later. They help children understand what event “caused” what outcome (cause-and-effect relationships). Narratives can help see a story from someone else’s perspective, something that does not come naturally to children. They aid in vocabulary development because stories require more complex language than day-to-day conversations do. Therefore, when they are exposed to storytelling, and are given opportunities to narrate their own stories, children develop conceptually, as well as in terms of oral language.

What is interesting about narratives is that both oral and written language contain stories. So if a child has been exposed to storytelling in the oral form, she can apply the knowledge of how stories work in the written form. In that sense, it serves as a useful bridge from orality to literacy.

Many Western scholars have studied how children’s sense of narrative develops in oral language. However, not as many people have examined how narratives develop in children’s writing; nor is there much work that shows links between children’s oral and written narratives.

The Literacy Research in Indian Languages (LiRIL) Study

From 2011-2016, my colleagues and I conducted a five-year longitudinal study in Yadgir district (Karnataka) and Palghar district (Maharashtra) to understand how children learned to read and write. In the course of this study, we showed pictures to children (Grades 1-3) and asked them to write a story about the picture. We did this exercise six times during the course of three years – twice each when they were in Grades 1, 2 and 3. We also showed 24 second graders a wordless picture book (The Story of a Mango, NBT) and asked them to orally narrate the story in the book. Thus, we were able to understand how children’s oral narratives relate to their storytelling in the written form.

Children’s Narratives in Oral and Written Forms

What we found was not very surprising, but was still interesting – there was a close (though not perfect) relationship between the kind of narratives that children wrote, and the narratives that they told. Let’s take a close look at this relationship with examples from three children’s storytelling attempts. All the children from Palghar district, Maharashtra, and they were in the middle of second-grade when we collected these samples. Their responses were in Marathi, but we have translated their orality to English and have translated their written attempts to Hindi and English so that audiences across the country can understand them.

Rasma’s Stoytelling Attempts

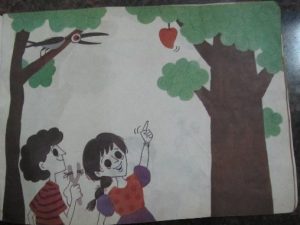

“Rasma” is a child who scored quite poorly on various reading and writing indicators collected during the LiRIL study. When Rasma was shown The Story of a Mango and asked to narrate the story, we noticed that she resorted to labelling the elements in the picture, rather than telling a story. Figure 1 shows an example of a page from this book where a girl spots a ripe mango hanging from a tree in Frame 1, and in Frame 2, she points out this mango to a boy with a slingshot.

Figure 1. Girl points out mango to boy with slingshot.

Rasma responded to the picture as follows:

Rasma: Tree, girl, mango.

Researcher: And?

Rasma: Boy, girl, bird, branch, rubber, leaves on the tree…nothing else…bangles.

Researcher: What else can you say?

Rasma: Leaves, branches of the tree, to kill the bird (pointing to the slingshot), girl is pointing her hand.

What can we observe about Rasma’s orality? We notice that when shown a wordless picture book, Rasma is not able to narrate the story that the pictures are telling; rather, she labels the pictures in words and phrases.

Now, let’s take a look at her writing. Figure 2 shows the picture prompt given for her writing.

Figure 2. Picture prompt for writing.

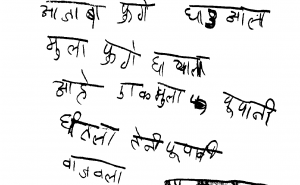

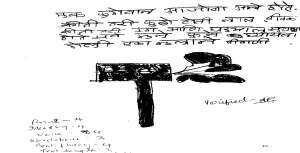

Here is what Rasma wrote in response to seeing this figure.

Figure 3. Rasma’s Writing.

What do we notice about Rasma’s writing? It is well known that young children often use invented spellings in their early writing attempts, so that is not surprising. But what did strike us is that when shown a picture and asked to write a story about it, Rasma resorted to the strategy that she had used orally, as well – of labelling the elements of the picture, rather than narrating a story!

Darpana’s Storytelling Attempts

Let us now look at Darpana, a student who was rated “average” on various reading and writing indicators used in the LiRIL study. How did she fare? We showed Darpana The Story of a Mango and asked her to tell us the story in the book. Figure 4 shows two pages from the book.

Figure 4. Girl points out mango to boy; bird snatches mango on a tree with a beehive.

Here is what Darpana said in response to the two pages shown in Figure 4.

Darpana: The boy made the mango fall. The girl watched.

Researcher: And?

Darpana: The crow started eating it….The mango…the mango fell. There are bees. That’s all.

What do we notice about Darpana’s storytelling? Is it different from Rasma’s? In what way? While Rasma labeled elements in the picture, Darpana’s narrative is a little more elaborate. She is describing events/actions shown in the picture, in sequence, but what we notice is that there is still no sense of a story, or plot. For example, in the first frame of Figure 4, she doesn’t mention the bird eyeing the mango; and she is not able to predict what might happen with the beehive. She simply narrates a sequence of events.

How does this student write? Figure 5 gives us a glimpse.

Figure 5. Darpana’s Writing

Again, we see a close parallel between Darpana’s attempts at orally narrating stories and her ability to narrate them in writing. She describes events in sequence in which there is no evident plot.

Mukund’s Storytelling Attempts

Finally, let’s look at the storytelling attempts of Mukund, a “high” performer on multiple literacy indicators assessed in the LiRIL study. How does this high performing boy fare in narrating stories?

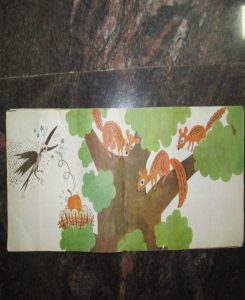

Figure 6 shows a single frame from The Story of a Mango, and Mukund’s oral narrative surrounding just this frame.

Figure 6. Crow drops mango into a nest full of eggs, while squirrels watch.

Here is what Mukund said in response to the picture:

“The crow was stung by the bees (seen in the previous picture). He started screaming. The mango fell into the nest. There were many, many trees there. There was a small nest. There were also many eggs. The bees stung the bird. On that tree, there were also many, many squirrels. The squirrels notice that in the midst of the eggs is one small egg. And, there was one big egg. How did the big egg get there? That too, a yellow and red egg! One squirrel remembered that this was the mango!”

When we analyze Mukund’s orality on this picture, we notice that the narrative is quite advanced. He has gone beyond describing a sequence of events, to imagining and narrating a story. For example, the part about the squirrels thinking about the strange looking egg in the nest, is something that has come out of his imaginative reading of the picture. He also built a plot related to the story when reading across the pictures of the book.

How did he fare in his writing? Figure 7 gives us a glimpse.

We notice that Mukund’s storytelling is more constrained when he writes, as compared to his oral narrative. We can classify this as a “basic” narrative, where the story has a beginning and a middle, but a very abrupt ending. There is some elaboration of ideas (e.g., the colors of the balloons), but not a very rich plot.

The Development of Narratives in Children

Several Western scholars (e.g., Applebee, 1978; Stadler & Ward, 2005) have identified a sequence in which children’s ability to narrate stories develops. The LiRIL study has validated the existence of such sequences in Indian children’s narration of stories – both orally, and in writing. Here is the sequence that we were able to observe (adapted from Stadler & Ward, 2005):

- Does not respond

- Labelling pictures – no narrative (e.g., “girl”, “boy”, “tree”)

- “Heap stories” - Reading actions in single picture frames – no connection between pictures on different pages (“bird is flying”, “man is sitting”)

- “Sequence stories” - simple text-based narrative is present—but usually focused on characters. Plot may not be accurately re-told. (“This story is about cats and rats. The cats are chasing rats.”)

- “Basic narratives” - Able to comprehend and re-tell narrative at basic level (main idea, plot, characters). Story may or may not have a coherent ending.

- “True narratives” - Able to re-tell narrative at advanced levels (with supporting details, inferences about character’s emotions, etc.).

Sadly, most children on the LiRIL sample were not able to go beyond reading actions in single picture frames, with no connections between pictures on different pages. In other words, they were reading pictures, but they were not telling stories. We noticed that the written attempts of most children in our sample, even at the end of Grade 3, were characterized by:

- Lack of connectedness or structure; no development of storyline

- Poor/routine vocabulary

- Lack of voice

It seems as of the curriculum was failing children in teaching them to write. But, more importantly, our data suggests that it was also failing to develop a sense of coherent orality in children’s attempts at telling narratives.

Implications for the Classroom

A sense of narrative appears to be a foundational knowledge-base that children could use flexibly across their oral and written work. I have tried to show here that children’s ability to tell stories in writing is heavily dependent on their abilities to tell stories orally. This, in turn, is likely dependent on whether they have had many chances to listen to stories read or narrated by others around them. Clearly, our data point to the idea that students in Indian classrooms don’t get many such opportunities – to listen to stories, to tell stories, or to write stories. This is a real loss for their language and conceptual development. So, one clear implication is that children in pre-primary and primary grades need to be given more such opportunities in their classrooms.

A second implication is that teachers need to become aware of the relationships between oral and written language development, and use these to strengthen children’s writing. Strengthening orality is important to strengthening writing.

A third implication can be derived from Mukund’s example, where his oral narrative is more advanced compared to his written story. This suggests that while strong orality is necessary for strong writing, it may not be sufficient. Even children with good oral skills may not become good writers unless given lots of guided practice with writing. Leaving them to do “free writing” or “creative writing” may not be enough. Most children need to be guided in understanding, analyzing and producing good narratives.

I would like to end by pointing out that while I have focused on the development of the narrative genre in this piece, ideally young children would also need to be similarly coached in other genres of writing. The narrative is an obvious and convenient place to start!

Appreciate the effort. Finally school is melting and community knowledge is gaining ground.

I did not count exactly how many times I nodded while reading this, but it was safely ‘a lot’! The examples were very helpful as was the article…