The Child Beyond The Threshold

Looking at the way the child is portrayed in children’s literature reveals underlying assumptions about a child’s capacity or lack of it to be autonomous and independent. Attitudes towards authority and learning become evident in the way relationships between child and adult are described, both in the family or in school.

Sudhir Kakar in his book, The Inner World: A Psychoanalytic Study of Child and Society in India details how hierarchical the family structure in India is and how little autonomy children have to make their own choices. He writes, “We know that if a child is praised and loved for compliance and submission, and subtly or blatantly punished for independence, he cannot easily withdraw from the orbit of family authority during childhood, nor subsequently learn to deal with authority other than submissively.” (1991:119-120.)

In a more recent study about adult-child relationships Bisht documented responses by parents and teachers when asked about the role of the child.[1] The dominant perspective was that the child is emotionally immature, vulnerable, dependent and incompetent. Adults largely saw their own role towards children as mentors, protectors and monitors of their behavior.

The pressure on the child to submit to adult authority and be mentored is reflected in a number of children’s books published in India and comparatively few books position the child acting outside the family sphere. In an interesting unpublished study of CBT books Meenu Thomas describes how the child accepts uncritically the decisions of parents.[2] She cites a number of books as examples of this which include The Toy Horse (1997) by Deepa Agarwal, A Present for Papa (2003) by Sharmila Kantha and Bravo Kamala (2011) by Alaka Shankar.

Typically – but particularly in text books - children are shown conforming to the family’s expectations: they have ‘good habits’, study hard, say their prayers and do not ask too many questions. They rarely move away from the protection of the surrounding adults in family or community. There is also a tendency to show the rewards of obedience and conformity so that the explicit moral in many children’s books is to accept dependence.

Yet there has been a strong counter- narrative of a child who is subversive, critical of social norms and poses awkward questions and challenges adults to re-think beyond conventional norms. It is refreshing to find in ‘the possible worlds’ created by some adult authors of children’s literature representations of a child who is resilient, insightful and a receptive learner.

In the long tradition of stories, songs, poems and dramas about Bala Krishna his naughtiness has been celebrated, He crosses every boundary of social correctness. The child Krishna disturbs and disrupts order; he lies, steals, breaks and spills things but it is these same qualities that make him so endearing. The child Krishna reminds adults that there is a meaning beyond a conformist, limited life of being bound by other people’s rules and regulations.

Thomson Press (1974)

Below I will discuss several books that offer an alternative to the dominant, sentimental view of the child who is dependent, passive and naive. These include some of the earliest publications of children’s literature in India and also some more recent books.

The Little Big Man, Rabindranath Tagore. Art by Rajiv Eipe. (2011) New Delhi: Katha.

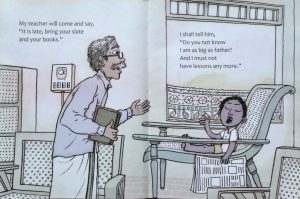

Tagore’s poem, ‘The Little Big Man’ was first published in 1913 in the collection of poems called “The Crescent Moon”. It is a translation from the original Bengali by the poet himself. The poem has recently been published in the format of a children’s picture book. The illustrations highlight the poet’s capacity to enter into the imaginative world of the child. In this poem the child is momentarily liberated from the authoritarian figures that make decisions for him – the teacher, the uncle, his parents – as he imagines his response as an equal adult. Each time the child is confronted with the expectation of dependency he counters the suggestion with how he is in charge of his own life and the adult acknowledges the justice of it.

The encounter with the teacher is one example.

My teacher will come and say,

“It is late, bring your slate and your books.”

I shall tell him, “Do you not know I am as big as father?

And I must not have lessons any more.”

My teacher will wonder and say,

“He can leave his books if he likes, for he is grown up.”

This capacity for ‘make-believe play’ gives the child a possible world beyond the present and an opening to forge a new layer of identity. The child enjoys a sense of his own power and the illustrator shows a child full of delight and confidence at a new-found freedom. There is an unexpected reversal in roles and the pictures revel in representing a child at ease with his own choices and the adult disarmed by the child’s logic.

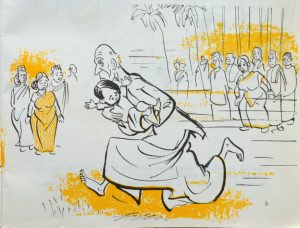

Life with my Grandfather, Shankar Pillai. (1967) New Delhi: Children’s Book Trust.

This book was the first publication of the CBT and is written by one of the most creative pioneers in Indian children’s literature. One striking aspect of the book is how Shankar captures what is going on in the child’s mind beyond the external events. The narrative is insightful because it is very close to the author’s own autobiographical experience and this gives the text a rare authenticity. The stories are set in rural Kerala in the early part of the 20th century.

The book recounts a number of Raju’s adventures but his mischief is never malicious or destructive. One of the incidents is entitled ‘The Snake Bite’. The irony is that there was no snake bite but only a bee sting. The grandfather panics on seeing a blue mark on Raju’s finger and fails to listen to the child’s logical explanation. Instead, he rushes to a healer to get the child ‘cured’ before a crowd of fascinated onlookers. Raju is a silent observer of what is happening but it is he who is most aware of the facts. He notices the folly of his grandfather, the incredulity of the bystanders and the shrewdness of the healer. There is a strong sense of humour as the child tolerates the rituals knowing full well that no purpose is served except to relieve his grandfather’s anxiety. The author, the child and the reader share the inside story!

In this book Shankar crystallizes the delight and wonder of the young child as he learns about the natural world and the dynamics of social relationships. The child, in this narrative, learns best not through explicit teaching but through his own ability to observe and reflect. Despite the misunderstandings and even confusions Raju trusts his family’s affection but also his own intuitions.

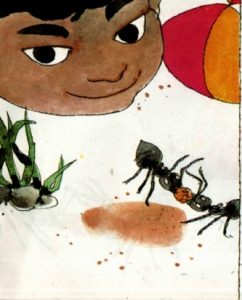

Busy Ants, Pulak Biswas. (1987) New Delhi: National Book Trust.

There are not many examples in literature of children actively engaged in learning about the world independently and outside the school context. Busy Ants is one such book that shows a child totally absorbed in watching the antics of ants. The picture book has no words but the pictures convey the child’s concentrated gaze as he observes details of the ants’ behavior. So much of our knowledge is gained second-hand through books or internet but here we are presented with a child’s disciplined, patient and careful study of nature face to face.

The book is particularly appealing because the pictures represent the child’s perspective of the scene. We see the ants from the child’s vantage point as the child stretches out on the ground to gain a better view. The child is motivated by his own compelling interest and no rewards or incentives are offered or required. No adult is represented in the book and the whole focus is on the fascination of the child’s interaction with the ants. The boundary between work and play is blurred and the child’s capacity for engagement and undivided attention is celebrated.

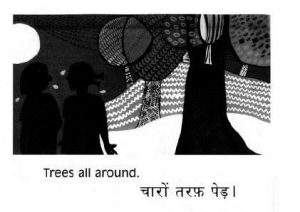

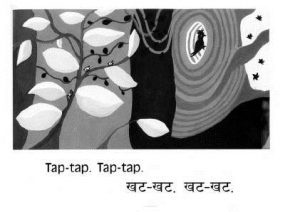

Night, Junuka Deshpande. (2008) Chennai: Tulika Publications.

In this unusual book a boy and a girl explore the beauty and the mystery of the night in the forest. Here too, similar to the child in the Busy Ants, the children are engrossed in the immediacy of the present moment. The minimal but evocative text and suggestive forms capture the impact of the surprises as they hear the sounds of the night and catch fleeting images of wild life. The children are totally receptive to the sensory experience of stillness and movement, light and shadows and there is no hint of fear or anxiety.

This journey through the moonlit forest is a time of enchantment but deeply rooted in actual experience. The children are alert and attentive but they do not need to speak to each other to intuitively enter into this extraordinary experience of the ordinary, natural world.

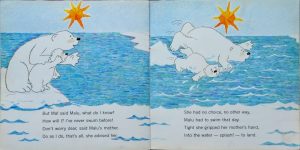

Malu Bhalu, Kamla Bhasin. Illustrated by Bindia Thapar. (1999) Chennai: Tulika Publications.

Malu Bhalu was first written in Hindi. The author introduces the book as a story written together with her son, Chotu following a shared reading of another story about polar bears. This story describes the adventures of an independent polar bear cub. The author writes, “This book, then, is dedicated to the carefree, fun-loving, whimsical wanderer and seeker hidden inside each one of us.”

Many texts for children hint at the dangers of taking risks to explore the unfamiliar world beyond the threshold of the safe home. Malu Bhalu’s adventures in her attempt “to see the world” and find “where the sunbeams danced” very nearly ended in disaster. The mother bear who pursues her missing daughter does not scold her when she finds her stranded on an ice floe. Nor does the mother threaten to confine her in the future but instead actually prepares the adventurous cub to cope with the challenges of survival by teaching her to swim.

Rumniya, Rukmini Banerji , Illustrated by Henu. (2007) New Delhi: Pratham Books.

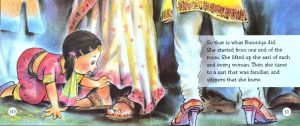

This book portrays a child who is confident to find her mother in the midst of a crowded wedding celebration. Traditionally a child is not solely the responsibility of the immediate family members but the community as a whole has a caring role towards its younger members. The child here seems to sense that she is not in danger even though she is temporarily separated from her mother. Rumniya sets about the search for her mother in a focused and unfazed way, confident that she is in the midst of a sympathetic but non-interfering community.

The appeal of the book lies in the way the illustrator shows the world from the child’s perspective. From an adult’s point of view the normal course of action for a person who is lost is to search for a familiar face but here we see the unlikely but sensible way the child crawls on the floor to identify the shoes of her mother!

This recent story is refreshing in showing a child alone and confident. It is in sharp contrast to the growing anxiety about the constant need for monitoring children’s movements in the urban context. Few middle-class children are independent enough to go to school unaccompanied and parents, for example, often feel compelled to escort their children to and from the school bus stop. Children frequently are warned to avoid any encounters with strangers and many families would feel they are failing in their duty if they did not protect their sons and daughters from getting lost.

In another book by Rukmini Banerji called Going Home (Pratham Books. 2004.) a young girl is shown confidently negotiating the chaos of city life as she rushes home from school in order to have time to play and to meet her father. In contrast to the sheltered and restricted life of the average middle class, the child in this text is a feisty young girl who weaves her way through heavy traffic and crowded streets unaccompanied. She shares the same determination and sense of purpose as the young Rumniya who is engrossed in her search for her mother.

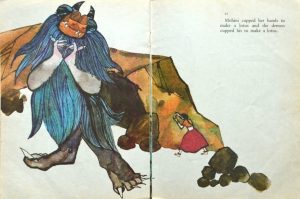

Mohini and the Demon Shanta Rameshwar Rao. (1990) New Delhi: National Book Trust.

Mohini and the Demon is a myth re-told. Interestingly, in this version the young Mohini is a girl that a child reader might readily identify with. She is the only person in the village who is not afraid of the demon, Bhasmasura who threatens he can reduce any human-being to ashes with a touch on his victim’s head. She considers the situation, “ I’m sure there’s a way out of this. I’m quite, quite sure. If only we could find it.” After careful thought she fearlessly confronts the demon and offers to teach him to dance as a trick to bring about his own destruction. Cleverly Mohini demonstrates the movements and unwittingly the demon destroys himself by placing his own clawed paws on his head as he follows Mohini’s dance.

Mohini begins the journey back to tell her grandmother but on the way is greeted by the villagers who then “carried her home in triumph”. In this story all the adults are paralyzed with fear and Mohini acts alone to save the entire village not through magic but cleverness and bold thinking.

Conclusion

In the books mentioned above each one in diverse ways portrays the child as an intrepid, explorer of his or her surroundings. The child is eager to venture beyond what is safe and known and is resilient even in the face of danger or the unfamiliar.

In most of these texts the adult plays a minimal role and even in Malu Bhalu where the mother rescues her cub she plays a supportive and not an authoritarian role. In a couple of the texts such as Shankar’s Life With Grandfather the child demonstrates a surprising maturity in contrast to the adult who seems to lacks sense and wisdom. In Mohini and the Demon it is the young girl who is ready to take risks and in order to defeat the menace of a ruthless monster and so succeeds in savings the community.

In these texts the child is not represented as a ‘savage’ that needs moulding and shaping, nor is there a romantic view of the ‘natural’ child unsullied by culture. The child’s innocence and playfulness is distinct from naivety and there is often a healthy realism that underlies the child’s view of the world. The child is also not wholly defined within the context of the family, educational institution and cultural norms of society but instead maintains a certain confident independence, curiosity and capacity to learn.

Loved reading the blog. Thought of Ulti sulti Mitto and Ulti sulti Amma by Kamla Bhasin as well.

Thank you so much for the wonderful article. I would like to know if a child can be left to figure out the world on his/her own independent imagination? How should be balance adult guidance and a child’s independence?

This is in response to Siddharth’s thoughtful query about balancing a child’s independence and an adult’s guidance in learning. I would like to begin by saying that in the blog I wrote about children’s capacity for independent thinking I was focusing on an often neglected aspect of how children can be close and astute observers and strongly motivated learners without explicit monitoring by adults. This is not to say that adults and peers do not have a very significant role in a child’s development and growth but only to draw attention to a child’s healthy curiosity and receptiveness to experience and the processing of that.

It is a matter of concern that children’s space and time is increasingly being monitored and determined by adults. This is often justified by legitimate but sometimes excessive concern about health and safety issues. Often children move from the structured learning situation of school to more of the same in the tuition class and are left with little time for pursuing their own particular interests or enjoying unsupervised play and investigations. A child’s capacity to give concentrated and sustained attention to something could potentially be the vey point where an adult’s sensitive guidance is most appreciated and enabling.

It would be interesting to explore through children’s literature another dimension of teaching and learning where children and adults interact in a creative and positive way. I am reminded of Gerald Durrell’s account of his experiences in “My Family and Other Animals “. The ten year old Gerald , an eager , budding zoologist is delighted to discover a mentor in Theodore Stephanides a Greek scholar who leads him into a deeper and more informed understanding of natural history on the island of Corfu..

Adults clearly play multiple roles in supporting children’s learning both implicitly and explicitly. In “Nabiya” by Chatura Rao we see a teacher who encourages a tentative, shy learner or in Maheshweta Devi’s “The Why-Why Girl” we recognize a model of a teacher who asks timely questions and is ready to respond to children’s doubts and enquiries.In “Tomas and Library Lady’ by Pat Mora we see the vital role of an adult in giving access to the rich resources of a library to a child who otherwise would not have had exposure to a world of books. Yet another positive aspect of child-adult interaction is shown in Nandini Naya’s book, “Pranav’s Picture” where the author traces a mother’s intuitive, non-judgmental response to her son’s attempts at drawing .Madhuri Purandare in her book, “Our School” describes from a child’s perspective how school can be an exciting place of learning and discovery.

Language itself can only be practiced through social interaction so we do not learn in a vacuum but by building on layers of shared human experiences and breakthroughs in the course of history. For example, we learn to tell stories by hearing or reading others’ stories.

I wonder if we could share other examples in children’s literature of how learning is nurtured.

Jane Sahi

January 2018

Please share the paper by Meenu Thomas citing my book ‘A Present for Papa’ as an example of a book inhibiting a child’s independence. In fact, the picture book shows the protagonist as the decision-maker in selecting a gift for her father’s birthday while her baby brother delights in being naughty. It would require a high degree of misinterpretation to consider the interaction in a negative manner.