Phases of Word Reading

The previous blog post, ‘Nature of Scripts’, explained that most Indian languages use alphasyllabic scripts, unlike English which uses an alphabetic script. Marathi and Kannada are examples of languages that use alphasyllabic scripts. A feature of many Indian scripts is that for every sound, there is a unique symbol. While this makes the sound-symbol correspondences very regular for young readers and writers, it also makes the task quite daunting in terms of the sheer number of symbols to be mastered. In Marathi and Kannada script, there are at least 49 symbols (the number varies a little by language) called aksharas. In addition, there are 14-16 secondary symbols to represent different vocalic sounds called “maatras” in Hindi. The maatras get attached to the basic aksharas to produce unique configurations. Further, there are additional symbols to represent conjunct consonant sounds called “samyuktaksharas” in Hindi. Thus, students have to master an extensive set of symbols to read and write these scripts fluently.

The Literacy Research in Indian Languages (LiRIL) project longitudinally tracked students as they encountered and mastered the Marathi and Kannada scripts from Grades 1-3. Thus, we got an opportunity to closely observe children move from emergent literacy skills towards fluency. Work done in the Western context with children learning to read and write in English had alerted us to the idea that there may be discernible “phases” that children go through as they learn to read words (Ehri & McCormick, 1998). Phases are characteristic ways in which learners read scripts at particular developmental levels and display both what they know and what they don’t during that period of time. Ehri and McCormick identified five phases of reading that young children go through as they learn to read the English script:

- Pre-alphabetic: Children have very limited knowledge of letters and attempt to read words by looking at pictures, or guessing from context.

- Partial alphabetic: Children begin to detect certain letters within words, and read by combining knowledge of context with knowledge of the sounds of familiar letters.

- Full alphabetic: Children know all or most of the sounds for different letters. They engage in letter-by-letter reading at this point, and therefore can be quite slow at reading.

- Consolidated alphabetic: Children begin to read in slightly larger chunks. For example, in English, they may be able to read –ing, or –ed as a unit, as well as other familiar groups of letters. Words are no longer decoded letter-by-letter. They are also able to read by analogy (e.g., “pat” looks like “cat”; or “peak” looks like “beak”). They are also able to read more words by “sight” – for example, “the” is read as a unit, and not letter-by-letter.

- Automatic phase: Children become fluent or “automatic” in reading both familiar and unfamiliar words and have a variety of strategies for decoding unknown words.

We were curious to see if we could identify similar phases as children learned to read Marathi and Kannada, because if we could identify systematic developmental progressions, curriculum, pedagogy and assessment could be designed to support them. To find out, we tracked the word and passage reading of 48 students (24 from each state) as they moved from Grades 1-3. We observed how the child approached the reading of words, the nature of the errors and the kind of strategies used for word reading. Not surprisingly, we were able to find discernible phases in word reading in these Indian scripts, as well. In many ways, these phases resembled the phases identified in the West, but due to the unique nature of our scripts, they also differed from them in certain ways.

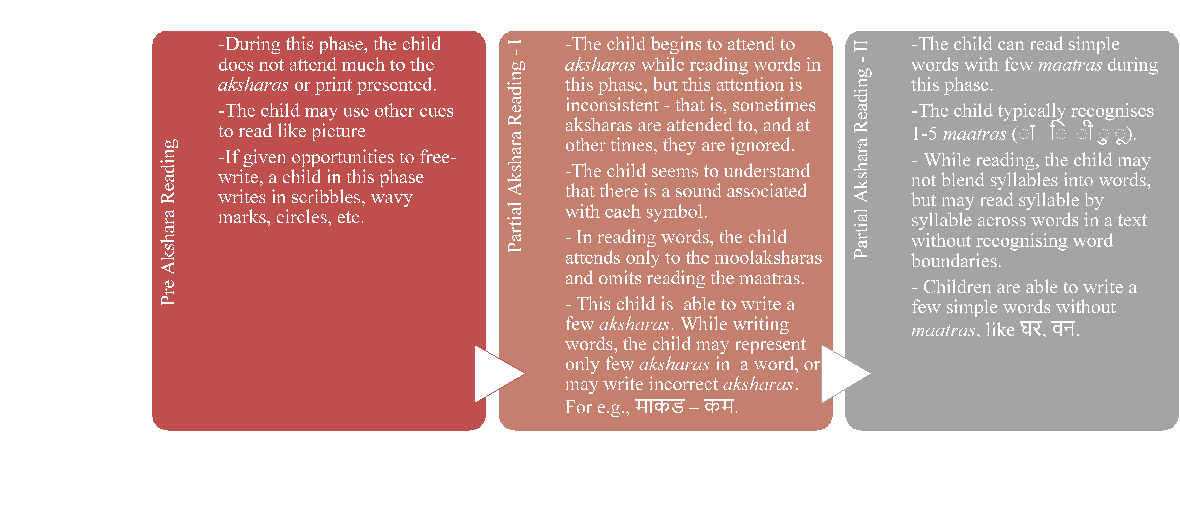

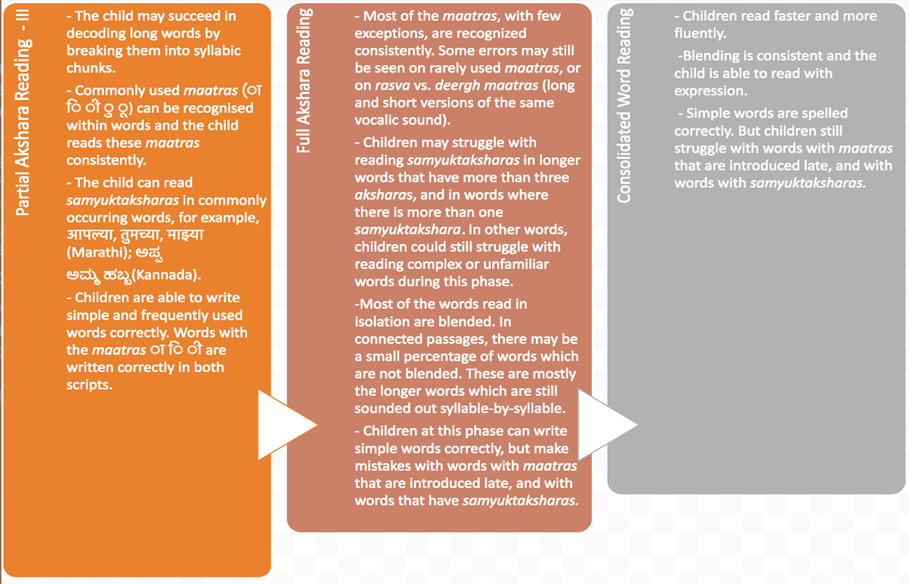

It is possible that the phases that children go through as they begin to read a script could vary depending on how children are taught to read the script. It is possible that an instructional programme that introduces the script in a very different manner from the ones we have observed may result in a different set of patterns of how children learn to read words. At the same time, we observed the same phases at both the sites that we studied – Karnataka (which uses the activity-based Nali Kali curriculum) and Maharashtra (which uses the textbook based Balbharati curriculum). This suggests that there is some robustness in these phases, and they could be useful to many educators working across the country. In this blog piece, we present a brief description of these phases (see Figure 1)[2].

Figure 1. Phases of Word Reading in Kannada and Marathi.

As we can see from Figure 1, the phases identified for word reading in Marathi and Kannada bear some resemblance to the phases identified by Ehri. It appears that while learning to read and write scripts, most children start by not understanding that the script needs to be attended to. They may try to make sense from the pictures or other accompanying cues. Later, children begin to understand that the script needs to be attended to, but it takes them some time to move from partially attending to it and attending to (and mastering) the script fully. After they master the script, they work at becoming fluent at it – that is, they can read it automatically, at a good pace and with expression.

The main differences between English and the Indian scripts is in how much time the child takes in going from “partial” to “full” mastery of the script. Ehri described this as a single phase in her work, while we were able to distinguish at least three sub-phases that children go through as they learn to read and write Marathi and Kannada. The main reason is that Indian scripts, as mentioned earlier, have an extensive set of moolaksharas, along with secondary vowel diacritics (maatras) and symbols for conjunct consonant sounds (samyuktaksharas). Predictably, children don’t learn all this at one shot. Initially, they attend to moolaksharas and fail to recognise or write maatras. Even when they start attending to maatras in words, they don’t attend to all equally. They learn the ones introduced earlier, which tend to occur more frequently in words. Likewise, when they start becoming familiar with the samyuktaksharas, they are able to decode words with one or two such symbols, but longer words with more such symbols are often stumbling blocks for young readers.

We reiterate that we do not have evidence to state that these phases are natural or universal among all young readers and writers of Kannada and Marathi. What if the maatras were introduced early and taught along with the moolaksharas at the beginning? Would young readers, then, show a different sequence of phases? It is possible. Our claims are limited to the data set we have from the two sites and methods of teaching that we studied. Yet, since these methods of teaching are prevalent across India, we believe that the phases have some implications for teaching the script.

Implications

The first implication is that teachers should be aware that children don’t learn the script all at once. Predictable errors that children make should be understood as developmental markers of where the child is, and should be used to help the child progress.

A second implication is that more time than is currently allotted needs to be spent on teaching children to read and write Indian scripts. We found that very few children in our sample were at the “consolidated” or fluent phase of word reading even by the end of Grade 3. This suggests that children may take the first four or five years of schooling to acquire fluency with our scripts.

Third, it is strongly recommended that maatras be introduced along with moolaksharas in early grades, so that children learn to attend to both kinds of symbols simultaneously. Samyuktaksharas used in common words (like: amma) can be introduced as “sight” words early on.

Specific recommendations for helping children at different phases could include:

- Very young readers can be encouraged to notice the text and the script. For example, teachers could point to the text while reading aloud picture books, so that readers notice that the symbols need to be attended to.

- Children who have begun to attend partially to aksharas can be cued to break words up into sounds and encouraged to identify: the sounds they begin with and end with, and all the sounds they hear in the word. This will help them better attend to the sounds in words.

- Games could be devised where words are presented without any maatras. Children who are not attending fully to maatras can be challenged to “spot the error” and insert maatras into the given words.

- Children can be asked to “sort” words given to them on cards into words with different kinds of maatras or samyuktaksharas.

- Children can be taught to break up longer, more complex words into manageable chunks to read or spell them.

- Children who are at the full aksharic phase can be encouraged to begin reading short passages with expression and speed.

- Children can be paired. The task of the first child would be to read in a flat, expressionless manner. The partner would then have to read the same passage with expression and speed. The pair can switch roles for the next round.

- Teacher modelling is necessary at all points. Teachers need to model that they (a) attend to the text while reading; (b) attend to ALL aksharas while reading; (c) read with fluency and expression; (d) and whatever else you want the child to learn has to be modelled and supported in the classroom!

These are just a few of the many ways by which teachers can support children in becoming competent and fluent decoders of the script. Of course, decoding the script is just ONE vital aspect of a balanced literacy curriculum, so do remember to keep enough time for other important aspects as well!

[1]This blog piece has been adapted from the findings of a longitudinal research project (Menon et al., (2017). Literacy Research in Indian Languages (LiRiL): Report of a Three-Year Longitudinal Study on Early Reading and Writing in Marathi and Kannada. Bangalore: Azim Premji University; and New Delhi: Tata Trusts).

[2] This is a brief summary. For a more complete description of the phases, please refer Menon et al., (2017). Literacy Research in Indian Languages (LiRiL): Report of a Three-Year Longitudinal Study on Early Reading and Writing in Marathi and Kannada. Bangalore: Azim Premji University; and New Delhi: Tata Trusts.