Comprehension in the English Classroom in India

For the vast majority of Indian children, English is not one of the home languages. Even for most of our city children, during the early years, there is hardly any English in the environment. Yes, a few English words have entered their Telugu and their Kannada -- schoolu and booku, for example. And some English words get used idiosyncratically -- fullu malé! (heavy rain!). But not much beyond that.

Added to that is the teacher’s own situation. As Gandhi noted in 1938 of his teacher: “His own English was by no means without blemish. It could not be otherwise. English was as much a foreign language to him as to his pupils” (Gandhi, 1999, p. 280).

All this sets up special challenges in the English classroom in India. How is the teacher to create conditions for improved English comprehension? Indeed, how is the teacher to enhance their own English comprehension? What about the learner’s considerable linguistic resources in their home languages? Can these resources somehow be harnessed to aid English comprehension?

This essay makes four proposals to address some aspects of these questions. The first proposal is based on the idea of “comprehensible input”. The second deals with “free voluntary reading” for the learner as well as the teacher. The third and fourth proposals draw upon the child’s and the community’s rich linguistic resources.

Input Hypothesis

Stephen Krashen argues that “we acquire a new rule by understanding messages that contain this new rule. This is done with the aid of extralinguistic context, knowledge of the world, and our previous linguistic competence. This Input Hypothesis explains why pictures and other realia are so valuable to the beginning language teacher; they provide context, background information, that helps make input comprehensible” (Krashen, 1989, p. 9). This immediately suggests that the content of the textbook and the supplementary material should be experientially familiar to the learner. This also suggests a classroom pedagogy which draws upon the linguistic competence the child already possesses. Some examples of the kinds of activities suggested are in our description of the Natural Approach.

The Natural Approach

The input hypothesis also claims that “the ability to speak ‘emerges’ on its own, as a result of language acquisition, as a result of obtaining comprehensible input… This hypothesis explains why children often go through a silent period lasting as long as several months before they begin to speak a new language” (Krashen, 1989, p. 9). This suggests a teaching strategy that does not insist on production (speech) from day one; that allows the learner to build competence before performing. A related method is the Natural Approach: “class time is devoted to discussing topics of interest, games, tasks and the like. Students may respond in either the first or second language, and their errors are not corrected; the comprehensible input from the teacher, not the students’ production, causes acquisition… Very little student talk in the second language is expected during early stages (termed the pre-speech stage). Activities are done in which students only need to answer “yes” or “no” or use someone’s name in order to participate. Gradually, more response is called for, but in general, students are not forced to speak” (Krashen, 1989, p. 14).

FVR

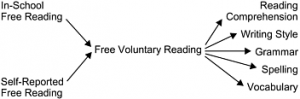

Our second proposal of “free voluntary reading” (FVR) also comes from Krashen: "reading because you want to: no book reports, no questions at the end of the chapter. In FVR, you don’t have to finish the book if you don’t like it. FVR is the kind of reading most of us do obsessively all the time" (Krashen, 2004, p. 1). He brings together evidence from many studies to show that FVR has multiple benefits at many levels of language-skills. The following figure sums up the benefits (Krashen, 2004, p. 17):

It should perhaps be emphasised that this recommendation of free voluntary reading applies with equal, if not greater, force to the teacher as well! The Teacher as Reader is a key component in improving English comprehension of the learner. Thus, workshops for teachers to (re-)discover the pleasure of reading may be a good idea. (Over the years, several teachers have sadly noted, “I used to be an avid reader at one time!”) Facilitating the setting up of a Reading Circle for teachers which meets, say, once a month, to exchange thoughts on texts that all the participants have read may be another doable idea. Ideally, these should be multilingual Circles, that share the joy of reading across many languages. Further, it may be possible to use social media (like WhatsApp groups) to keep the Circle active even during the period between meetings. Different formats will be needed for different groups.

Activity Webs

Our third proposal relates to activity webs that draw upon the learner and the community’s language resources. The following example adapts Abraham (2018) for our present purposes. The lesson objective was to teach Kannada-speaking 11-year-olds to identify, over two 45-minute classes, the subject and the object in English sentences, and learn to convert active into passive voice in simple sentences. In the first, preparatory class, students form simple sentences about themselves in English as well as in Kannada; they list their favourite festivals and favourite foods. A printout of a festival dish is given with the recipe in English in active voice. Homework consists of finding out from family members the ingredients and recipe for their favourite festival food. They then write the recipe In English, and also write a few sentences about their favourite food. In the second class, they learn to transform their sentences and the recipe into passive voice. Activity webs like these that build community involvement into their design use the multilingual resources widely available for English-language learning in India. They also seek to mitigate the alienating aspects of English-learning in non-English environments.

Identity Texts

The fourth proposal involves a longer class project, that of creating “Identity Texts” (Leoni, et al., 2004). Immigrant 13-14 year-olds in Canada with varying degrees of ability in English and the heritage language (Urdu) collaborated to produce narratives of their lives in a book they co-authored called The New Country. The book compared and contrasted life in Canada with life in “the old country”. This, of course, meant that the children drew upon the experiences of others in the family and the community. The involvement of the community and the peer learning during the project resulted in enjoyable English-language learning, while at the same time reaffirming the learners’ multiple linguistic and ethnic identities. As the authors note, “When the classroom becomes an ‘English-only zone’, much of students’ existing knowledge is, unfortunately, likely to be banished from the classroom along with their home language” (Leoni, et al., pp. 49-50). For one account of the perils of proposals for an English-only education in India, see Rao (2017), who concludes, “English must remain a part (but only a part) of the country’s multilingual ecology.”

These four proposals outlined above suggest that the multilingualism of the learner and the teacher are vital resources in improving comprehension in the English classroom. Strategies that encourage cross-linguistic transfer need to be built in into every level of the language-learning process -- from curriculum and textbook to pedagogy and assessment.

References

Abraham, F. (2018). Lesson plans to teach Kannada-speaking 11-year-olds two aspects of English grammar. Unpublished MA assignment for the course “Teaching English Language in India”, Azim Premji University, Bengaluru, India.

Gandhi, M. K. (1999). Higher education. Harijan 9th February 1938. Reprinted in M. K. Gandhi. 1999. The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi (Electronic Book), Volume 73, pp. 278-283. New Delhi: Publications Division Government of India. Retrieved from http://www.gandhiserve.org/cwmg/VOL073.PDF

Krashen, S. D. (1989). Language acquisition and language education: Extensions and applications. Hemel Hempstead: Prentice Hall International.

Krashen, S. D. (2004). The power of reading: Insights from the research. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

Leoni, L., Cohen, S., Cummins, J., Bismilla, V., Bajwa, M., Hanif, S., Khalid, K., & Shahar, T. (2011). ‘I’m not just a coloring person’: Teacher and student perspectives on identity text construction. In J. Cummins & M. Early (Eds.), Identity texts: The collaborative creation of power in multilingual schools (pp. 45-57). Stoke on Trent: Trentham Books.

Rao, A. G. (2017). English in Multilingual India: Promise and Illusion. In H. Coleman (Ed.), Multilingualisms and development (Proceedings of the 11th Language and Development Conference, New Delhi 2015) (pp. 281-288). New Delhi, India: British Council. Retrieved from http://www.langdevconferences.org/publications/2015-NewDelhi/Chapter17-EnglishinMultilingualIndiaPromiseandIllusion-Rao.pdf & https://www.academia.edu/31367701/A_Giridhar_Rao_-_English_in_multilingual_India_Promise_and_illusion_2017_