Children making sense of writing

One thing that children seem to learn efficiently in almost every school is how to write, or more precisely how to copy a script. Children are expected to copy increasingly lengthy answers into their notebooks from the blackboard, from a guide or from each other. These efforts are often not even corrected by a teacher but by a monitor in the class. The children are not necessarily expected to read what they have written and even less to comprehend it. A recent experience of working in a Government aided Kannada medium school with 4th standard children revealed that about half the class were hardly able to decode what they had copied and a few did not seem to have grasped any concept of a letter-sound relationship.

In this scenario writing becomes a mechanical and time consuming exercise that is disconnected from any purposeful learning. This mastery of writing or copying does have a symbolic significance because the community and the children themselves recognize that this skill is identified with power and status but its benefits as a tool for empowerment may remain out of reach if children remain unable to read what they write or write without a purpose.

Vygotsky argues that written language is often taught in an artificial and mechanical way that is inappropriate for the young child. He concludes his essay entitled ‘The Pre-history of Written Language’, by saying, “Children should be taught written language and not just the writing of letters.”[1]

Perhaps one of the reasons for children’s difficulties in writing in a meaningful way is that too quickly a young child is propelled into writing before they have actually made the connections between the spoken word and its visual sign. This leap into literacy - in the fullest sense may be particularly difficult for children who have little exposure to print within a meaningful context outside the classroom. If a young child does not have the experience of seeing print in use at home or in the community such as watching a parent or sibling make sense of the newspaper, a wedding invitation, a hoarding or an application form then the child may need extra support to see how print works and why it has its uses.

The situation may be further aggravated if the child is writing in an unfamiliar language such as English or the dominant regional language which is not spoken at home or in the community. If children cannot speak with any comfort or ease the language which they are expected to write then they are placed at a severe disadvantage. This is likely to become worse as the demands for writing increase as the child moves from grade to grade; the child may not even expect to understand any meaning beyond complying with the teachers’ requirements.

The challenge is to find ways to support children in the classroom to go beyond merely copying so that the links between the spoken word, reading and writing are made. A young child’s first markings – lines, dots, loops and spirals - in sand, on paper or slate with stick, finger, pencil or chalk can be the beginning of a young child’s exploration into communicating visually.

These first “scribbles” can move in many directions. For example, gradually the forms may take on a shape or movement that the child can name as something particular. For example the child described this picture as “playing in the sand”

The scribbles may also begin to resemble letters or numbers that the child may have seen at home or in school. Below we can see a range of markings that the child is playing with as patterns. The markings are placed in relation to each other but not in a conventional form that we recognize as standard writing.

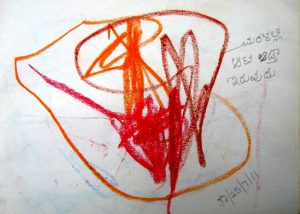

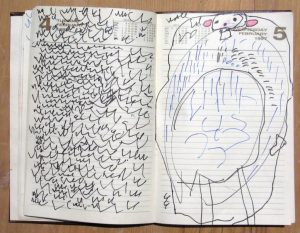

In time the child may take more steps to imitate some of the conventions of writing. Note in the picture below we can see a clear sense of orientation from left to right following the conventions of the writing of many languages. It should be noted that writing in different languages can be orientated very differently such as Urdu or Arabic from right to left, Chinese in vertical lines etc. We can also see some variety in the symbols used even though these may be of the child’s own making.

Another significant step is when the child attaches meaning to his or her emergent ‘writing’ In other words an insight into the notion that what is spoken can be written down and preserved. In relation to the following picture the four year old girl replied when asked what she had written by saying that it was a poem but it was a secret! This is no longer random scribbles but evidence of a growing sense of the link between visual signs, sounds and the word.

The child’s first image making often includes pictures and letters and numbers and there is not a sharp distinction between drawing and writing. It is fascinating to note that Chinese there is a different development where the image is crystallized to represent not the sound but the word itself.

In the classroom apart from providing opportunities for children to experiment with markings, image making and imitation writing and valuing these developmental steps the teacher can also make explicit the links between the written word and what it represents. Children’s names are often a powerful starting point. Other ways of making these connections would be to label things in the classroom or to make a display and label objects children have selected on the way to school or in the natural surroundings.

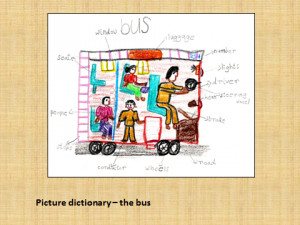

Picture dictionaries also help children to see the written word in a meaningful context.

Children might also collaborate to make a frieze of a story and label the key characters or each write a key sentence to tell the story.

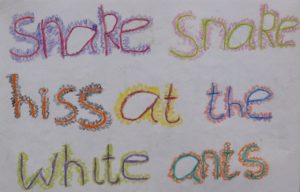

The children should be able to read what they write whether it is the sentence that they have generated, a part of a jingle or a tongue twister. It helps sometimes for children to write the words in different colors so that they can point to the word and see that words are within a flow of language but also separate.

A line from a chain story

Sometimes it is possible for teachers or helpers to act as scribes. This may be writing down significant words that the child wants to collect as Sylvia Ashton Warner suggests in her descriptions of what she calls “organic writing”[2]. Children can also dictate captions for their pictures or longer texts that tell of their experiences or own stories. Young children are sometimes surprised by the magic of hearing their own spoken words when their stories are shared aloud.

Children gain confidence in writing if they are ‘allowed’ to make mistakes and teachers do not demand perfect, unduly lengthy ,standard writing too soon. Children are often required to write much in excess of what would be helpful. One strategy that ensures all children try to write independently is for them to write freely what they want to express and then, if needed, the child dictates what they have written and the teacher makes a correct copy below without scarring the child’s own efforts with red ink.[3] This can provide the child reading material that is built on and extending their own experiences. R t also serves as a good indicator for the teacher as to how to support the child to become a more proficient writer.

The skills of good handwriting, correct spelling and clarity in expression are vital for children to learn but if that is to be accomplished then it must be through the child engaging with reading and writing in a meaningful and personal way that makes sense to the child and is motivating for the children to grow in skills of communication and comprehension.

[1] Vygotsky L.S. (1978) “The Pre-history of Written Language” in Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes ed.M.Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, and E. SoubermanJohn-Steiner, S. Scribner, and E. Souberman. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

[2]“ Teacher” by S. Ashton Warner

[3] I l first observed this process at PSS in Phaltan, Satara District when Dr Neelima Ghokale displayed children’s work of this kind.

Jane Sahi

March 2018

Many good ideas here: thank you!

Thank you so much for this piece. The practical suggestions are very helpful, too. In my limited work with children in early grades, I have observed that children feel far more comfortable and motivated to write in “free-writing” sessions when we’re available to write down the spellings they ask for instead of just saying that spellings don’t matter and that they should only focus on sharing their experience ( and that they can write whatever spellings seem correct to them). I found some validation for this practice in John Holt’s essay “Making Children Hate Reading” (The Under-achieving School). What’s more, at the end of such a session, this board full of words becomes a game for children and they try to read out as many words as they can off of it.

Thank you again for such a compelling piece!