OELP's Approach to Building Script Knowledge in Beginning Readers and Writers

Background

OELP’s (Organisation for Early Literacy Promotion) Early Literacy Project developed as an exploratory search to seek correlations between marginality and academic underachievement in reading and writing as they play out in formal schools and out-of-school spaces. The interventions within this project were built on our earlier experiences with young children who read and write mechanically in school and are unable to make any sense of what they are reading and writing. We were keen to engage with emerging literacy learners who are also new school entrants.

The idea was to explore feasible options that are available inside classrooms to address some issues related to learner underachievement in early literacy. Our focus was on the processes of reading and writing as they unfold inside classrooms and to explore ways in which these can be strengthened.

It was also important to us that the interventions that evolve be grounded within the multiple and layered complexities of classrooms. These classrooms often reflect the stratifications within the larger social world they are located in, and we found many young learners to have already internalised their place in the social world by the time they entered school. A majority of the children who attend these classes are from low-literate backgrounds and, most often, they do not have access to supportive reading and writing environments at home or in their social worlds.

The early years have been globally acknowledged to be the most critical for lifelong development. Therefore, this project was initially spread across Classes 1, 2 and 3 of six Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) schools on the outskirts of the city.The children who attend these schools come from various parts of the country. This provided us with the opportunity to engage with learners from diverse linguistic and socio-cultural backgrounds.

After a year of sustained work within this urban context, our project was relocated to government schools in rural Rajasthan, where it continues. This is a drought-prone landscape where low-literate communities eke out a livelihood through daily-wage work, pastoral activity, subsistence farming or petty trade. The main language spoken in the area is Marwari, while Hindi is the medium of instruction.

The Broad Framework

Through our engagement in classrooms and with research-based literature on early literacy and language learning, we identified some broad indicators as a framework to guide the evolving classroom pedagogies and practices, and to allow conceptual clarity to emerge. These indicators are listed below:

- Address the special needs of children who are engaging with the written forms of language for the first time when they enter school. Many of these children are not conversant with the language of classroom transaction and require support to be able to engage in the class.

- Provide a balance between a structured programme for building script knowledge and opportunities for children to freely and actively explore written texts in a variety of ways.

- Utilise the inherent character of the Devanagari script, which is a transparent alphasyllabary and also provides a symbol for each spoken sound.

- Link reading and writing activities to the children’s home languages and real-world experience so that the process of acquiring script knowledge and decoding skills becomes meaningful and relevant for each learner in ways that are developmentally appropriate.

- Equip children gradually over two years to make a transition from their home language to the language of classroom transaction so that they can engage in class in meaningful ways.

- Provide children with a responsive and active classroom learning environment with opportunities to engage with written and pictorial texts through planned as well as informal and authentic reading and writing opportunities.

- Provide opportunities for strengthening reading comprehension and higher order thinking skills, supported by rich and interactive classroom conversations.

- Involve the class teachers in the process of developing classroom practices.

The focus of this work has been on the learning needs of children from low-literate homes who are also emerging literacy learners interacting with print for the first time when they enter school. This places them at a major disadvantage as compared to their peers from better off homes who have had opportunities to engage with print-based activities in their early childhood years. The OELP classroom practices draw upon children's real-world experience and spoken language resources to facilitate meaningful shifts from oracy to literacy. Our aim is to equip these beginning school-goers to become thinking and engaged readers and writers, and to make decoding a meaningful part of this process.

The Evolution of OELP's Classroom Practices

The classroom practices within the OELP project have evolved organically over a period of time through sustained interactions with children and teachers inside classrooms. These practices include linguistic skills required for engagement with the sounds and symbols of the Devanagari script as well as the cognitive skills required for meaning construction and higher order thinking. We have considered both these aspects of script knowledge equally important and addressed them simultaneously.

We also recognise the importance of providing young learners with a conducive socio-emotional climate in the classroom as an essential and non-negotiable condition for facilitating learning. Our classroom experience has confirmed that a learning environment needs to be non-threatening, stimulating and responsive to the individual needs of children from diverse socio-cultural and linguistic backgrounds. This ensures that children experience school positively and engage with classroom processes in meaningful ways. Through such engagement many children become confident learners with a positive sense of self, regardless of their social backgrounds and home environments.

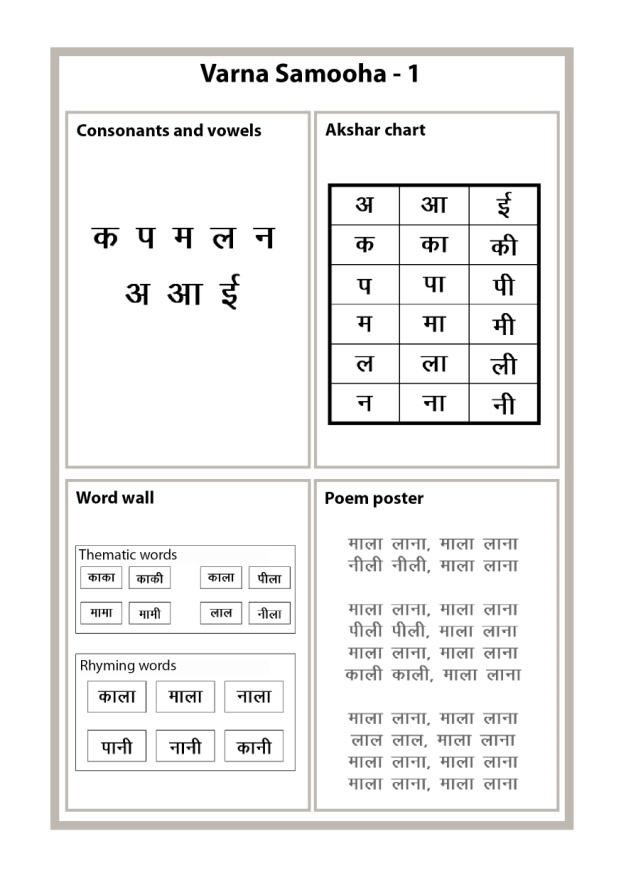

We began work through the Hindi Bara Khadi which was an unused resource available in the classes. It provides the various sound-symbol combinations available within the Devanagari script at the phonemic, alphasyllabic and syllabic levels. Through our initial interactions we experienced that the Bara Khadi had too much information for the children to process and was becoming a tool with which they were engaging in a very mechanical way. This led us to the idea of breaking down of the Bara Khadi into smaller groupings or Varna Samoohas. These varna samooha evolved over time as sets of a limited, select number of alphasyllables, vowels and abbreviated vowel markers or matras.

The varna samooha groupings evolved over one academic year through an organic process of intensive and sustained engagement inside the early grade classes of a few government schools in which our Early Literacy Project or ELP (as it was called then) was being implemented. The selection of the specific sub-lexical components within each grouping was done through an active process of dialogue with teachers. Teachers and members of the OELP team used their intuitive knowledge and experience with young learners to select the components for each varna samooha. This was followed by a process of trialling inside classrooms and revising based on the children's responses.

While constructing the first two varna samoohas, we looked at the distinctiveness in the sounds and visual topography of each symbol from the Devanagari script used for written Hindi. Teachers also engaged with a broad sense of the frequency of occurrence of the specific sound-symbols in Hindi and to some extent in the spoken languages of the children. An important consideration was the ease with which these sub-lexical units combine to generate words which are from within the children's spoken language repertoire and life experience. While making the selections of the components for the first varna samooha, we looked for combinations that allow children to locate words that are closely connected to them and are personally meaningful. For example, words used for the generic names of family members or the names of colours. Some teachers looked for sound-symbol combinations which generated rhyming words or sound patterns since they said children of this age group enjoy word play. So the children's natural learning behaviours also became a part of the selection criteria in informal and intuitive ways.

As explained, the selection of the sub-lexical components for each varna samooha was an organic process which unfolded through our efforts to make decoding a meaningful process for young learners. We were keen to allow phonological and orthographical awareness to unfold within the language ecosystems in which the children in these early grade classrooms were building their script knowledge. In the situation of adapting this approach to other language offshoots of Devanagari, the existing components within each of the six varna samoohas may be reviewed so that they address the linguistic demands of the language being considered. To give a recent example, we supported a partner organisation from Gujarat to adapt the varna samoohas to their context. During this process we ended up making minor modifications in each varna samooha, and to some extent, in their chronology. This enabled us to align with the phonology, orthography and vocabulary of spoken Gujrati in more nuanced ways. We believe that these adaptations are likely to make the engagement with the varna samoohas more meaningful for the Gujrati-speaking children who will engage with them in their classrooms.

The Varna Samooha Approach

The varna samooha approach focuses on the following:

1. Phonological and Orthographical Processes for exploring and building awareness of:

- The sound units within spoken language

- The sound-symbol relationships within written language

2. The Processes of Meaning Construction for understanding of the sound-symbol-meaning relationships within written language, so that children are able to experience meaningless symbols as parts of familiar, meaningful written words.

Within the Devanagari script, the linguistic unit that is most akin to spoken sounds is the akshara or alphasyllable. In most schools, children are taught to decode written Hindi through the varnamala. The varnamala is described by some scholars as an inventory of alphasyllables and phonemes that represent the sounds of the Devanagari script arranged in terms of their place of origin (bilabial, dental, palatal etc) and their manner of articulation (aspirated, un-aspirated and so on). In most schools, children memorise the varnamala and then use it to engage with structured word lists in predetermined ways. Through our interactions with young learners and individual reading observations inside classrooms, we experienced that since the varnamala does not always represent the sounds that children hear, it can become a stumbling block for beginning learners attempting to decode words in Hindi. Let us take the example of the word paanii (water). Our experience suggests that children are able to clearly identify the sounds that are heard at the syllable level, namely: paa and nii - and then match them with their symbols. However, in most schools, children are taught by fragmenting the word into: /p/ /aa/ /n/ /ii/, i.e. the sound units within the varnamala. Since these are not the sounds the children hear, the decoding process, we have found, becomes much more challenging for them. Within the Varna Samooha Approach we have regrouped the sound-symbols from the Hindi varna mala into six groups called varna samoohas. Each group has a limited selection of alphasyllables, vowels and matras as shown in the diagram for the first varna samooha. These varna samoohas have been designed to help children understand the linkages between sounds and symbols at the sub-lexical, word and text levels simultaneously, so that they can experience these in interrelated ways. The underlying thinking is that children should not view written sound-symbols as meaningless forms which they rattle off mechanically. Instead, they relate to these sound-symbols as parts of familiar words. This process occurs at increasing levels of complexity with available combinations increasing with the introduction of subsequent varna samooha.

Within the Varna Samooha Approach we have regrouped the sound-symbols from the Hindi varna mala into six groups called varna samoohas. Each group has a limited selection of alphasyllables, vowels and matras as shown in the diagram for the first varna samooha. These varna samoohas have been designed to help children understand the linkages between sounds and symbols at the sub-lexical, word and text levels simultaneously, so that they can experience these in interrelated ways. The underlying thinking is that children should not view written sound-symbols as meaningless forms which they rattle off mechanically. Instead, they relate to these sound-symbols as parts of familiar words. This process occurs at increasing levels of complexity with available combinations increasing with the introduction of subsequent varna samooha.

The varnamala can be introduced in Class 2 to familiarise children with conjuncts etc. A pictorial presentation of OELP's Varna Samooha Approach may be viewed through the web link:

A resource pack with supportive material for each varna samooha has been developed by OELP. This includes materials to support the implementation processes shared through the presentation. The resource pack also offers samples of activities and evaluation formats.

The Classroom Process

The children gradually learn to recognise the sounds and symbols of all the sub-lexical components being introduced within a varna samooha. First the alphasyllables are introduced, one at a time. The children engage with its shape and sound in a variety of ways. They engage with activities based on recognising the beginning sounds children's names or names of familiar objects. Next, the children are introduced to all the possible combinations that are available in the varna samooha through an akshara chart. There is daily recitation of this chart through actions that emphasise the short and long vowel sounds. This process helps children internalise these through physical actions which are game-like and enjoyable.

Gradually the children learn to actively manipulate the sounds and symbols available within an akshara chart and combine them to create written forms of their own spoken words. For example, a child may combine the sound-symbols maa and mii to construct the word maamii - a word for a person who is from within the child's lived experience, which makes it meaningful.

The existing varna samoohas also absorb words from other languages with a phonology akin to Devanagri. We have come across words made by children in Bhojpuri; Bengali; Punjabi etc., the languages they speak at home. It is fascinating to experience, at times, the exuberance of a child who has just actively constructed her first written word. Once it dawns on the child that this written form represents something from her real world – a family member, a colour, or some object - she is likely to get hooked! From this moment onwards, it can become game-like and akin to a treasure hunt for words for some children.

After a child constructs a written word from the akshara chart, she is required to draw a picture to illustrate its meaning. We consider this as an important step towards meaningful decoding. The visual representation of the word helps the child connect the written forms with the mental picture her mind, and her drawing makes the written word meaningful for her. Contrary to a word card with a picture already on it, as is often the case in language classrooms, the meaning that each child represents through a drawing is unique for that child. For example, in one class, the children’s drawings for the word paanii (water) varied from drawings of drops, a bucket, a tap, a river, and a glass, to an earthen pot. Each drawing gave us a glimpse into the unique mental image that the word had created for a particular child. Through these processes, each child begins to experience inner connections with the written words they construct. During such activities, the children’s spellings and drawings are not corrected. This allows them to experience a sense of ownership of their words.

It is important to realise that, through the above processes, children begin to actively experience the correspondence between the written and spoken forms of the words they construct. The akshara chart also provides opportunities for children to engage at appropriate developmental levels because of its inherent character that allows children to function at multiple levels. For example, some children construct simple bi-syllabic words by combining contiguous aksharas available in the chart. Their more proficient peers may, however, construct more complex poly-syllabic words combining aksharas from different locations across the same chart. So even though children are actively involved in the same activity, they may actually be performing at different levels of complexity. This makes it a useful teaching-learning material for multi-grade situations as well as a tool for assessing learner levels. Once the children have acquired decoding proficiency within one varna samooha, the next one is introduced through a predetermined chronological order, in a cumulative manner.

Some words constructed by the children are corrected by the teacher and are displayed in a word wall so that they are visible to the children all the time. We use these in daily word activities and games so that children engage actively with the written forms and meanings. Unlike the sight word or whole word approach, OELP does not provide children with predetermined word lists. This distinction is important as it highlights the active cognitive and linguistic processes used by the child to construct written words.

We have also created little poems and rhymes from the words within a varna samooha. These are presented to the children through poem posters which are displayed in the class. Children recite these rhymes / poems with actions. They learn to read them with the help of the akshara chart. It can be very motivating for a Class 1 reader who, after reading an entire poem, begins to feel that she is now a ‘proper reader'.

Giju Bhai, in his book Prathmik Shala Mein Bhasha-Shiksha, makes a reference to a phase in a young child’s reading and writing development which he calls “shabdon ki bahaar” or “springtime of words”. He describes the exuberance with which young children, who have been able to unravel the codes of the written script, want to engage with written words all the time. We discovered the same sense of excitement in some children’s active engagement with written words. If the teacher allows them to explore, they can be found enthusiastically looking for words from akshara charts. They compete with each other to find new words. They play word games. They engage with words in storybooks and classroom displays. We believe this is so because children begin to feel a sense of ownership and inner connection with the words that they create. This is empowering for them.

Creating a Facilitative Language Learning Environment in the Classroom

It is important to note that the varna samooha approach is not implemented in isolation. We have tried to capitalise on the classroom as an authentic social setting, or a living context within which children can interact with each other through the written form. We try to get children to actively engage with a variety of displayed print in the class. For example, children respond to each other through displayed messages; or use written words from the word walls to play word games or participate in word activities. They write and respond to displayed riddles in the riddle corner, at times in their home languages. They share displayed rhymes, verses or poems through reading and writing. They read, look at, and talk about pictures or displayed writings. They listen to stories being read aloud or read story books, and then share their ideas and opinions about the story. There is time in the class to engage in meaningful conversations. Children are helped to write, draw and respond to storybooks through reader’s response charts. They engage with curricular texts in meaningful ways. All of these become ways through which these young learners interact and communicate with each other in authentic and purposeful ways, through a variety of texts and textual materials. The wall spaces in the classroom provide children with opportunities to freely use their home languages and invent spellings in their own ways. Thus, the walls of the classrooms become like buffer zones which allow children to use print freely, without being afraid to make mistakes. The idea is for young learners to realise that reading and writing have deep connections with their lived experiences and inner worlds, so that they experience these as a means through which they can relate to their worlds, and to each other.

Conclusions

There are several challenges that OELP has come across, both in the urban and rural contexts. These have confirmed our belief that children who come from low-literate cultures need special attention. Our experience suggests that once children develop strong foundations in reading and writing within the first two to three years of schooling, they begin to engage more confidently with written texts. Our sustained engagement inside classrooms and with rural communities has reinforced the belief that if we want to regard schools as places where all children will learn, then it is vital that classroom processes engage with the specific socio-cultural and linguistic contexts within which learning can occur. This allows the processes of reading and writing to become relevant and purposeful for the learners. As young learners begin to engage more positively with texts, they begin to influence their teachers’ attitudes and beliefs about their capacities to learn, and a positive cycle of learning slowly begins to grow.

Keerti Jayaram

OELP, July 2018

mein bhi ye feel karta hu ki agar aap language class mein bacho ko jitne moke do bolne ke wo class utni hi achhi or class ko aage lejane mein madad karti hai.i like your concepts and what kind of environment developed in class room .i want to visit your class if possible .i think we learn more if we observe class room.